Few topics in the history of food and cooking have caused as much emotion and debate as the history of coffee bans. From its early days as a secret potion to its current status as a beloved drink around the world, coffee has been through a lot. Cultural, religious, and political forces have shaped its history. Come with us on a trip through time to learn more about the interesting story of coffee bans. Along the way, we’ll find stories of plotting, rebellion, and major changes in society. From the busy streets of Constantinople in the 1600s to the battlegrounds of today’s battles over caffeine laws, the history of coffee bans is as long and complicated as the drink itself. Hold on tight as we reveal the interesting story behind one of the most controversial drinks in history.

Many people think that Kaldi and his goats in 700 AD were the discoverer of Coffee and from there it all began. According to legend, the goat herder Kaldi found his goats behaving strangely. He found the peculiar behaviors of his goats were related to grazing on crimson berries. This discovery became the foundling beginnings of coffee as we know it today. Word of coffee and its effects quickly spread. Many states embraced coffee, whilst other was cautious of its properties. We will discuss few historical events of banning coffee by series of write-ups. Today we will talk about Mecca and Persia.

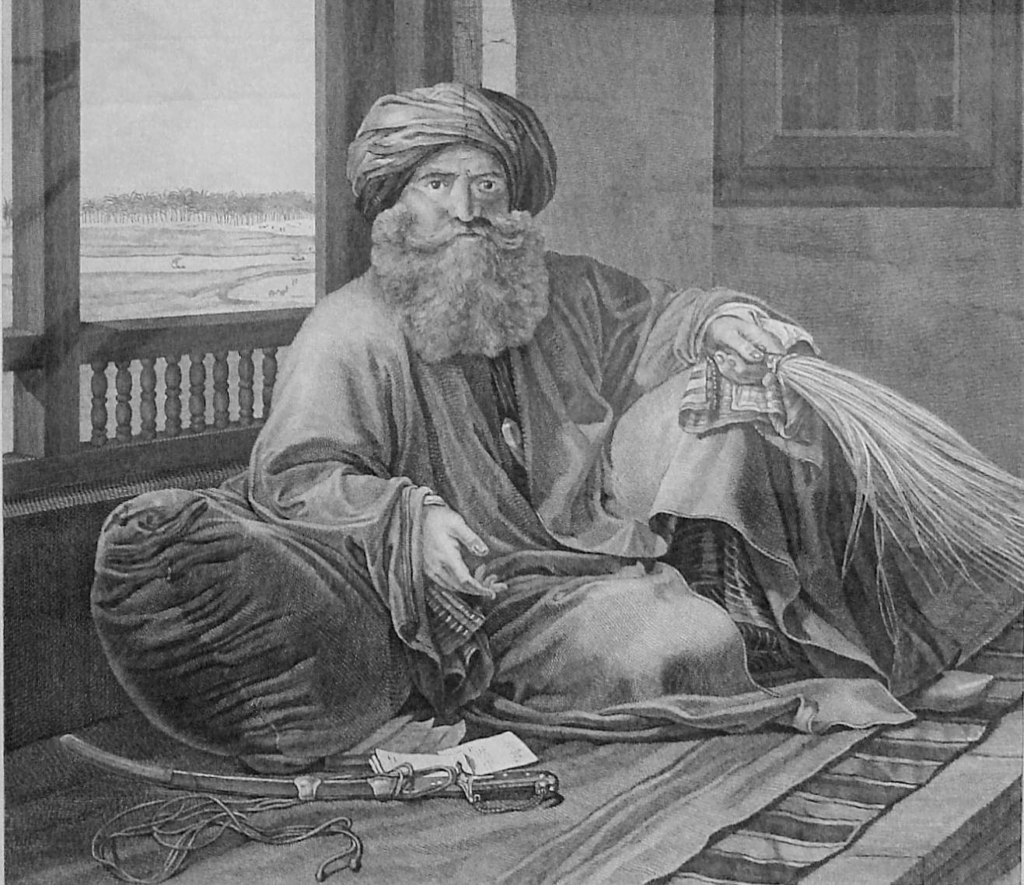

Photo © Wikipedia

Young Khair Beg, the governor of Mecca in 1511, demanded that all coffee establishments be shut down, in part because his medical advisors had advised him that it was harmful to people’s health. The governor’s main justification, though, was that he thought coffee encouraged radical thought and the assembling of like-minded individuals, which may help unify his opposition. At that time, anyone caught selling or consuming coffee received a beating. By order of Ottoman Turkish Sultan Salim I, the prohibition was finally lifted in 1524, and Grand Mufti Mehmet Abussuud al-mahdi issued a fatwa permitting coffee use once more. Beg was put to death for his misconducts by order of the Sultan, who also declared coffee to be holy.

Still, misunderstanding of coffee’s effects and fear of coffeehouses lingered—some saw them as seedy meeting places, similar to whorehouses. By 1535, religious critics were pointing to Islam’s Hanafi laws, which forbade drunkenness, as a justification to ban coffee again. But whether that concept of “drunkenness” included caffeine jitters depended on which school of Muslim thought they subscribed to at the time.

Two Iranian doctors also spoke out on favor of coffee skeptics a century after Khair Beg’s ban. According to Calestous Juma, the Kenyan-born Harvard Kennedy School professor, the doctors’ 1611 tract on coffee claimed the beverage had vile characteristics. They said the governor should receive “great glory and abundant rewards” if he opposed the drink, thus appealing to the governor’s desire for legitimacy and power as a ruler.

This disagreement about coffee’s properties continued a protracted debate about whether it was good for or bad for one’s health. The Encyclopaedia Iranica explores the dominant theories in Persia throughout the 16th century, which acknowledged both positive and negative qualities. The work of Mohammad Husssayn Aqil serves as an example of these opposing viewpoints. On the one hand, he claimed it was a laxative and diuretic that was good for the stomach, was helpful for decreasing blood pressure and for curing the majority of headaches, and could be used to treat smallpox, measles—especially when combined with pearls—and hemorrhoids. Coffee satisfied the thirst. It promoted healing of wounds when sprinkled on them.

Conversely, the negative consequences of coffee consumption were dryness of the respiratory passages, nightmares, pallor, and loss of sex desire, insomnia, heart palpitations, sadness, and headaches, if consumed in large quantities, it can even lead to brain issues, though ‘Aqil’ thought this would only happen if the beans were extremely stale and roasted to a dark color.

Even while this sounds unusual, others have come to the same conclusions about drinking coffee and have started their own bizarre advertising operations against it. These prohibitions frequently had religious and health justifications, but they also shared a concern for the substance’s “social qualities”—namely, its propensity to be sold and consumed in public gathering areas. It frequently denoted a location for scheming and rebellion against autocratic leadership.

[TBC]