Kahve was a favourite drink of the Ottoman Empire’s ruling class. Little did they know it would one day hasten the empire’s demise

According to the cultural magazine of The Economist, 1843 our favourite drink coffee somehow hastened the demise of the vast Ottoman Empire.

According to Sarah Jilani, a column writer in The Economist, ‘Coffee came to Turkey during the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. When the man he dispatched to govern Yemen came across an energising drink known there as qahwah, he brought it back to the Ottoman court in Constantinople, where it was an instant hit.’

To serve the seamless tiny cup of coffee or kahve, Ottoman palaces soon started to appoint a kahveci usta (coffeemaker) and his assistants (their sole work was to grind the Arabica beans into extra fine powder). The kahveci usta then boiled the powder in copper pots- cezves.

Jilani wrote, ‘The resulting drink – bitter, black and topped with a thin layer of froth created by pouring it quickly – was served in small porcelain cups. To balance its bitterness, legend has it, Seleiman’s wife Hurrem Sultan, took her kahve with a glass of water and a square of Turkish Delight- which is how it is served in Türkiye Cumhuriyeti today.’

An Ulama in Suleiman’s durbar issued a fatwa against this energizing beverage on the logic that pertaking anything burnt is forbidden. But this fatwa didn’t slow coffee culture, Jilani said.

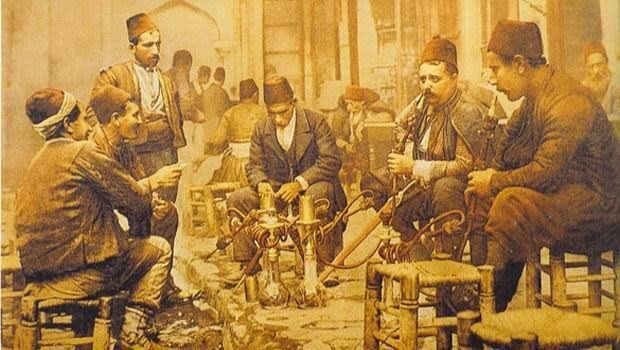

The first two entrepreneurs of Kahvehane or Public Coffeehouse in Istanbul were Syrians, and they opened those in the year of 1555. In a difference of few days, there were a boom, nearly one in every six shops in the city was a kahvehane and coffee began to spread farthest corners of the empire.

Jilani wrote, ‘Coffee houses gave men somewhere to congregate other than in homes, mosques or markets, providing a place for them to socialize, exchange information, entertain – and be educated. Literate members of society read aloud the news of the day; janissaries, members of an elite cadre of Ottoman troops, planned acts of protest against the Sultan; officials discussed court intrigue; merchants exchanged rumours of war. And the illiterate majority listened in. In the coffee houses or kahvehanes they were introduced to ideas that spelled trouble for the Ottoman state: rebellion, self-determination and the fallibility of the powerful.’

Authorities soon began to see the kahvehane as a threat. A major shift from today, when Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has vowed to open 24-hour coffeehouses across the country and the head of Turkey’s Religious Affairs Directorate says coffeehouses or kahvehanes are among the most significant establishments of Turkish civilization.

On that time, some sultans installed spies in coffee houses to gauge public opinion, while others, like Murad IV, an early-18th-century sultan, tried shutting them down, according to Jilani. But they failed, and coffeehouses came to play a little-known role in the collapse of the empire.

“When simmering nationalist movements came to a boil throughout Ottoman lands in the 19th century, the popularity of coffee houses burgeoned,” wrote Jilani. “Nationalist leaders planned their tactics and cemented alliances in the coffee houses of Thessaloniki, Sofia and Belgrade. Their caffeine-fuelled efforts succeeded with the establishment of an independent Greece in 1821, Serbia in 1835, and Bulgaria in 1878. The reign of kahve was over.”

You can read the original feature here: